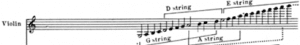

The violin is the soprano of the string instruments, with a range that spans from a low G below middle C (G3) to as high as the violinist can reach, usually around E7, or two octaves above the open E. The violin is tuned in fifths: G3, D4, A4, and E5. Each of these strings has a wide range, with the lowest pitch being the open string.

As the violinist climbs up the fingerboard, the pitches become successively higher, and part of a violinist’s virtuosity lies in the technical ability, versatility, and flexibility with which the violinist can maneuver between a wide range of pitches and strings.

Did You Know the Violin Started as a Dance Instrument?

A couple of factors opened up a wider range on the violin. For example, the current length of the fingerboard. This allows the violinist to climb up the higher pitches of the string. And the chinrest, which provides stability for the player. Before the standardization of the modern violin, the baroque violin had a shorter fingerboard. It also had a shallow neck angle, different bridge shape, and gut strings.

The violin historically started off as a dance instrument, providing a simple accompaniment to dancers. It gradually evolved in shape, form, and function as instrumental music came into its own. Gut strings were gradually replaced by “overspun” strings, which had a gut core wrapped in metal wire, allowing for sound to project, and the neck and fingerboard developed a steeper slope, which allowed the strings to meet the bridge at a sharper angle, increasing the pressure on the instrument.

The highly tense E-string was liable to break, until the metal E-string grew in popularity in the late 19th century. Eventually, steel strings came into common use for all four strings in the 20th century, replacing the more nuanced but temperamental gut strings, as projection, power and consistency became necessities for the modern concert hall, allowing violinists to compete with a large orchestra.

The Violin’s History is Complex

All this is not to say that the pre-modern era of violinists, composers, and their music was simple. Quite the contrary. Unlike the modern piano – epitomized to perfection in the modern Steinway whose hallmarks include its cross-stringing and cast-iron plate, and which is built on a wholly different mechanism from the early keyboard instruments – the modern violin has not changed much in shape or form from the early violins.

The “Renaissance violins” have a wide variety of shapes and sizes. And they served as accompanying instruments, and violins were used pretty much synonymously with cornettos, a wind instrument praised for its ability to imitate the human voice, but which gradually fell into disuse.

By the time the cultural apex of the baroque violin was reached, violins had come into being as solo instruments. By 1610, Giovanni Paolo Cima had written the first early examples of violin sonatas, showing the evolution of the violin into a solo instrument.

Violin Music Continued to Develop

As music for the violin developed, the capabilities of the violin shone forth and vice versa. Instrumental music became a vehicle of expression in itself, rather than as a support for the voice or as part of an instrumental consort. By the time of the High Baroque, violinist-composers were writing and displaying formidable violinistic displays of virtuosity.

Italian Virtuosos & Composers Were at the Forefront of Violin Range Development

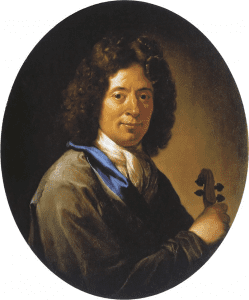

Italian virtuosos and composers were at the forefront. These included Corelli. His wide and far-reaching influence radiated outward into other countries through his music and pupils such as Geminiani.

Geminani’s treatise, the Art of Playing the Violin, was published in London, and a look at its examples and instructions show a familiarity with the entire range of the violin, from the lowest to surprisingly high positions in the upper ranges of the E-string, and display his technical prowess both in the left and right hands.

It was an influential treatise and a reference for violinists, composers, and theorists even after his death, for example Leopold Mozart, who cites it in his Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing. It is still an important reference for violinists today on phrasing, articulation, rhetoric, and period performance. Another Italian Baroque violinist-composer is Pietro Locatelli. He is well known nowadays for his capriccios, which feature technical challenges and leaps up to the highest ranges. And positions on the violin that rival Paganini’s 24 caprices.

Arcangelo Corelli Portrait by Jan Frans van Douven

The Italian Composers’ Influence Extended Far Beyond Italy

The Italian composers’ influence extended far beyond Italy into England and into the German-speaking countries such as Austria. There, a new crop of virtuosic violinist-composers also emerged, most famously in Heinrich Ignaz Biber and Johann Heinrich Schmelzer. Their compositions epitomize the stylus fantasticus, characterized by a free, fantastic, imaginative style of writing and playing unrestrained in form or style, marked by abrupt, unprepared, and frequent changes in character and mood.

The improvisatory and free nature of its affect lend itself well to a dazzling display of virtuosity and innovation. For example, its shimmering quick runs up to the high reaches of the E string. And its reach to the lowest ranges of the G string. Quicksilver jumps between the high and low ranges. And innovative use of unusual violin sonorities. Biber’s Sonata violino solo representativa includes imitations of different animals such as the nightingale, cuckoo, frog, and cat by using out-of-tune glissandos, rapid tremolos, harmonics, and scraping noises to name a few.

Biber’s Rosary Sonatas, which are an unusual example during this era of a programmatic, continuous cycle of movements set to a particular theme or idea (the Rosary), feature imaginative and brilliant sonorous use of the violin to create a stunning effect – to meditate on the life of Christ.

The Beauty of the Violin Lies Beyond its Range

The beauty and capabilities of the violin lie beyond its ability to reach the high ranges. Its unrivaled ability to imitate the human voice is magical. This has been cited repeatedly by theorists and violinists for hundreds of years. It also has infinite variety of tone color and an incomparably warm timbre. These combine to give the violin its unique ability to sing and give shape, beauty, and meaning to a phrase. Much like how light in a Vermeer painting illuminates a humble interior.

Akiko Kobayashi