The word harmony is derived from the Greek word Harmonia, the goddess of harmony and concord. As its Greek origins imply, harmony means concord, agreement, or a joining together, which happens when two or more notes sound together in a pleasing combination.

Harmonia’s counterpart, Eris, was the goddess of strife and discord, whose parallel in music, dissonance, happens when two or more sounding notes clash. Much like the goddesses of Greek mythology, harmony and its related sister, tonality, allow for conflict, balance, and resolution, all of which drive musical narrative and drama.

So, what is harmony?

It is the sounding together of two or more notes, whose vibrational frequencies create either a consonance or dissonance.

The Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras famously discovered that when a string of equal length is plucked, they sound the same (vibrational frequencies of 1:1); if it is divided in half, one hears the same pitch an octave higher (frequencies 2:1); if it is divided in thirds, one hears a perfect fifth between the two strings (3:2), and so on.

Out of this natural phenomenon arose the discovery of the harmonic, or overtone series, where each interval (distance between notes) was found to be the ratio of perfect integers. The purest intervals (such as the octave and fifth) were those closest to the fundamental, or original sounding note. And the more complex the ratio was, the more dissonant and colorful the resultant interval became. Consonant intervals imply stasis, stability, and resolution, whereas dissonant intervals imply tension, conflict, and instability.

Gregorian chant is based on this concept, as the interaction between multiple vocal lines creates a succession of consonant and dissonant intervals, all of which flow into one another to form a web of interacting voices that rise and fall in tension. The beginning and end of the chants open and close with the purest interval (unison or octave), providing a point of stability. This is the origin of the concept of harmony and a harmonic cadence, a rhetorical, harmonic flourish at the end of a phrase that provides closure and resolution, much like a period at the end of a sentence.

Harmonies, and Their Hierarchy of Importance

The interaction between melodic lines gradually led to the rise of vertical harmonies, which is the vertical relationship between two or more stacked intervals at any given point in time.

A hierarchy of importance and interrelationships arise from it, as certain harmonies are more stable than others, much like the fundamental intervals in the overtone series. Tonal music is based on the push and pull between stable and unstable harmonies struggling for dominance as they move closer to or further from a “gravitational center,” or tonality (Laitz, 2012, p.2). The farther one is from this gravitational center, or original tonal area, the more unstable and uneasy one feels and the more the listener expects and longs for a return to the original starting point. This is the concept of a home key, or tonality of a piece, and the reason why harmonies have a sense of direction.

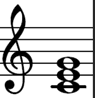

When two consecutive thirds are stacked on top of one another, a harmony called a triad is created.

For example, in C major, a triad built on top of the first scale degree, C, creates a C major triad:

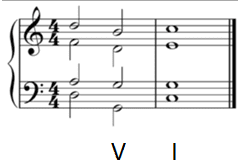

Within the tonality of a piece, harmonies have a hierarchy of importance. A triad built on the first scale degree is called a tonic, and is designated by the Roman numeral I. Like the first fundamental frequency in the overtone series, it has the greatest degree of stability. In a tonality of C major, the tonic would be the C major triad, and in a tonality of A major, the tonic would be the A major triad, and so forth. Tonic has the greatest stability and sense of stasis, and is the starting and ending point of any classical tonal piece. Another important harmonic pillar in a piece is the dominant, designated by the Roman numeral V. It is built on the fifth scale degree.

So, in a C major tonality, the dominant would be a G major triad:

Like the second fundamental frequency in the overtone series (3:2, or fifth), this is the second most important harmony in a piece. Harmonies have an innate sense of direction, a pull towards or away from a destination. Any dominant harmony feels an inexorable pull towards the tonic, and hence, the cadence is born: a cadence, the rhetorical flourish at the end of a phrase, is simply a dominant going to a tonic.

You Can Hear Examples All Around You…

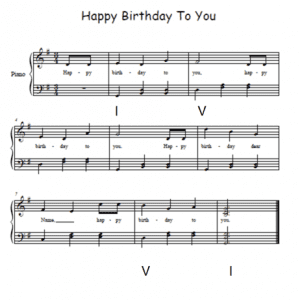

It is clearly discernible to the ear, for one senses a return to stability and familiarity when one returns to the tonic. Any simple melody contains the above V-I cadence: for example, the tune “Happy Birthday” ends on a cadence on the final words:

As can be seen in the simple melody above, pieces start from the tonic, go to the dominant, and eventually return to the tonic at the end of a piece. Pre-dominant harmonies are the intervening harmonies between the tonic and dominant that feel a strong pull towards the dominant. They are harmonies built on the second or fourth scale degrees: respectively called the supertonic (ii) and subdominant (IV) harmonies.

To take the example of a C major scale, a triad built on D would be the supertonic and a triad built on F would be the subdominant. Every harmony has its own quality and color based on the quality of the thirds within the triad: a major third stacked with a minor third on top is called a major triad, and vice versa. To take the example of the C major triad, it is a major triad because C-E is a major third and E-G is a minor third. Minor triads have a darker and more unstable quality due to the minor third at the bottom – incidentally, a minor third is farther away from the original fundamental than the major third in the overtone series.

Composers Use These to Create Variety, Conflict, & Resolutions

Composers use these various characteristics of harmonies – its innate sense of direction and its inherent qualities – to create variety, conflict, and resolution, a characteristic which Beethoven used to magnificent effect. The famous 3-note opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony feels so uncertain and disorienting due to its lack of harmony and tonality: without a harmony, there is no context for the 3 notes (G-G-Eb), so it could be in Eb minor, Eb major, or c minor. When the cello enters, one finally has a harmonic context for the opening 3 notes, and we find out, to our relief, that the motif is part of a tonic triad (c minor triad):

This is the essence of harmony and tonality: it gives it a sense of orientation, homeness, and stability. Conflict arises when the distance from home, the tonal starting point, is extended and expanded. The play between stability and instability, conflict and resolution, expectation and surprise is the basis of all tonal music from the Baroque to the early 20th century. Without it, music would lose its direction and meaning, which is what gives music its powerful dramatic force.

References:

Laitz, Steven G. The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Tonal Theory, Analysis, and Listening. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Akiko Kobayashi