I’m so excited that you’ve decided to dive deeper into your musical studies with some music theory basics. Before we begin, I want to let you know that I teach multiple days a week on Takelesson Live. After reading the first article in this “Music Theory for Singers” series please feel free to come join me in a live class so that I can answer any questions you might have, and to help you better understand the material. This link will provide you with 30-days of free TL Live membership access https://bit.ly/3sFXGRQ .

Music theory, the language of music is used in countries all over the world. Music theory is written, read and played by people who speak English, Spanish, Italian, French, Mandarin, etc…

Music theory is using standard notation of notes on the staff. Just like vowels and consonants, verbs and nouns, there are several parts that work together to help the reader understand how to interpret the information on the page.

In the first part of this series, Music Theory for Singers, we’ll discuss how to read rhythms. Rhythm is the length of a note. Whether the note you are singing will be held for a short amount of time or a longer period of time. Rhythmic notation will also tell you when to be silent. Music is, in its most simplified definition, the play between noise and silence.

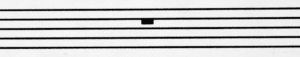

Staff Lines: On each page of music you will find a staff. A staff is a series of five lines that musical information, like notes, meter, time, etc.. is written on.

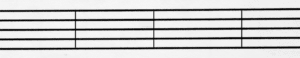

Measures: If there is a longer piece of musical information that needs to be conveyed through notes, the staff lines will be broken up into measures. Measures make music easier to read. The measures organize the notes into groups that are equal to the time signature that is indicated at the beginning of the page of music. In the diagram below you will notice the staff lines have been divided into 4 equal measures.

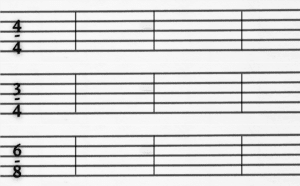

Time Signature: The time signature will be to the left of the first measure. The time signature will look like a fraction with one number on top and one number on the bottom. The top number will tell you how many beats can be in each measure. The bottom number tells you which kind of beats.

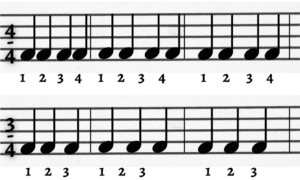

The first example shows 4/4 time. This means there are four beats in every measure. The top number indicates the number of beats in the measure. The bottom number indicates the type of beat. This is important because if I ask you to go to the store and pick up 4 pieces of fruit, you are going to pick up whatever you want. If I ask four musicians to count out 4 beats, each one of them would count a different type of beat. One might count longer beats (oonnee, ttwwoo, threeeeee, fourrrrr), another might count very quick beats (one2three4). In the instance of the first time signature the bottom number is letting the musician know that the 4 beats in the measure are quarter notes.

In the second example with the 3/4 time signature the top number is letting the musician know that there are 3 beats in each measure and the type of beats are quarter notes.

In the third example with the 6/8 time signature the top number is indicating that there are 6 beats in every measure. The type of note is an eighth note. This means 6 eighth notes worth of time can fit into every measure.

Keep reading for further clarification.

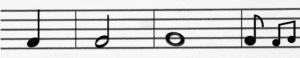

Types of notes: There are several types of notes that denote rhythm. For the purposes of this lesson we will cover the most widely used.

In measure one we have a quarter note. The quarter note is the “generic” length of time for one beat. When you hear a drummer counting in their band with a “one, two, three, four” he/she is counting 4 quarter notes. In a piece of music with a 4/4 time signature where there are 4 beats in every measure, and the quarter note is the type of beats we are counting, we could fit 4 quarter notes in the measure. This is because quarter notes occupy 1 beat of space, or a “quarter” of the measure.

In measure 2 we have a half note. A half note is worth 2 beats. In a piece of music with a 4/4 time signature where there are 4 beats in every measure, and the quarter note is the type of beats we are counting, we could fit 2 half notes in the measure. This is because half notes occupy 2 beats of space, or “half” the measure.

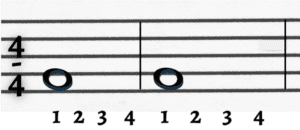

In measure 3 we have a whole note. A whole note is worth 4 beats. In a piece of music with a 4/4 time signature where there are 4 beats in every measure, and the quarter note is the type of beats we are counting, we could fit 1 whole note in the measure. This is because whole notes occupy 4 beats of space, or the “whole” measure.

In measure 4 we have 2 types of eighth notes. The first eighth note has a flag on it. It’s how an eighth note looks when it shows up by itself. The second pair of eight notes is connected by the flags. It’s how eighth notes look when they show up in pairs. An eighth note is worth one half of a beat. In a piece of music with a 4/4 time signature where there are 4 beats in every measure, and the quarter note is the type of beats we are counting, we could fit 8 eighth notes in the measure. This is because eighth notes occupy one half a beat of space each, or 1/8 of a measure.

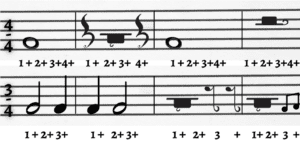

Counting notes in music: In the figure below we see quarter notes in the music with both 4/4 and 3/4 time signatures. In the 4/4 time signature we can see that there are 4 quarter notes in every measure because the top notes tell us how many beats we can have in every measure.

We would count these notes as 1, 2, 3, 4. 1, 2, 3, 4. 1, 2, 3, 4.

In the second line of music we can see 3 quarter notes in every measure. The 3/4 time signature lets us know that there can be 3 beats in every measure. The bottom number lets us know that the type of beats we are referring to are quarter notes. We would count these notes as 1, 2, 3. 1, 2, 3. 1, 2, 3.

In this next figure (below) we can see half notes in music with both 4/4 and 3/4 time signatures. In the 4/4 time signature we can see there are 2 half notes in measure one, while there is a half note and 2 quarter notes in measure 2. The top number in 4/4 times tells us how many beats we can have in every measure. If 4 beats can fit in each measure and a half note is worth 2 beats, we can fit 2 half notes in each measure (2+2=4). Alternatively we can fit one half note and 2 quarter notes, since each quarter note is worth 1 beat (2+1+1=4).

In 3/4 time we can fit 3 beats in each measure. In measure one we see 1 half note and 1 quarter note (2+1=3). In measure two we see 1 quarter note and 2 half note (1+2=3)

As long as the note values add up to the total number of beats in each measure (not going above or below the indicated amount of beats) you can mix and match the note values however you like. One of the many choices you get to make when you write your own music.

You’ll notice we still count 1, 2, 3, 4 1, 2, 3, 4 for 4/4 time and 1, 2, 3 1, 2, 3 for 3/4 time, but the amount of time each note takes up has changed. The half notes sound for 2 numbers (beats) each, while the quarter notes sound for one number (beat) each. If sung, measure one of the top line (the 4/4 time) would sound like this Laaa Laaa. While measure 2 would sound like Laaa La La

**Pop quiz: Could you fit 2 half notes into a 3/4 measure?

**Answer: No, 2 half notes would take up 4 beats. You cannot fit 4 beats into a 3 beat measure.

In the next figure (below) you will see 2 measures with a whole note in each measure. Because a whole note takes up 4 beats of sound you can only fit one whole note into each measure.

**Pop quiz: Why can’t you place a whole note into a measure of 3/4 time.

**Answer: A whole note will not fit in 3 beats of space. It will occupy more space than given.

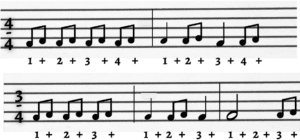

Lastly, take a look at the figure below with eighth notes in it. An eighth note takes up 1/2 a unit of beat. This means you could fit 8 eighth notes into one measure of 4/4 time or 6 eight notes into a measure of 3/4 time. Because an eight note takes up one half a beat it is important to subdivide the beat when counting. Instead of counting 1, 2, 3, 4. We would count 1and 2and 3and 4and. The “and” is symbolized by a “+” in the figure below.

We are taking a normal beat and dividing it into 2 sections. This makes the eighth notes easier to count and understand. There are still 4 beats in every measure on the first staff line and 3 beats in every measure on the second staff line, but more notes are happening at a faster rate between beats.

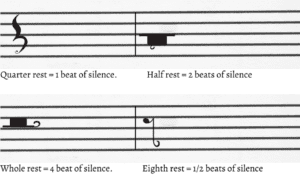

Rests: Rests are just like the notes that we’ve studied above, except they tell us when to be quiet. Below is an example of the rest equivalent to each note. Rests follow the same rules as regular notes. The notes/rests you use in each measure have to equal the total number of beats that are allowed per measure, as stated by the time signature.

In the following figure you will see rests used to convey silence between the notes. All the beats are subdivided into 2 parts to help with counting when you encounter eighth notes. Follow along and see if you can identify the name and value of each note and rest. Refer to all the diagrams provided for you and check to see if you got them right.

Conclusion: Take some time to go over the information in this text and then move on to part 2 in this series – “Music Theory for Singers” where we learn how to read pitches. And remember, If you are looking for live instruction, to further deepen your understanding of music theory, be sure to join me on Takelesson Live. You can also pop into one of my classes to check if you got the answers correct 🙂

Reina Mystique