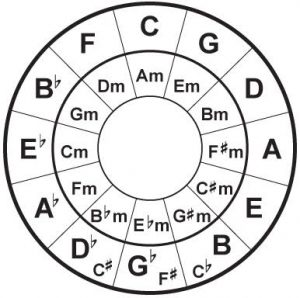

The circle of fifths is an extremely helpful diagram. It is used to understand how keys, scales, and chords relate to one another. Sometime I refer to the circle of fifths as “the mother ship” with my students, because the diagram really encompasses all of the basic elements of western harmony.

As a side note for more advanced readers, jazz players typically rearrange the circle of fifths to a circle of fourths. They like the circle to move from C major (no sharps or flats) to F major (one flat) to B-flat major (two flats), to E-flat major (three flats), etc. They do this because:

1.) Jazz is brass and woodwind oriented and horns prefer flat keys.

2.) A circle of fourths, moving clockwise, can be interpreted to follow the path of a ii-V7-I chord progression, which is common in jazz writing.

However, if you are a beginner to the concept of the circle of fifths, please don’t get hung up on the jazz interpretation. Let’s start from the beginning and describe what the traditional circle is.

Imagine the circle as a clock. The “C” on top is like the number 12. “G-flat” and “F-sharp” on the bottom is like the number 6. If you begin at “C” and move clockwise, you will see that the letters are each five steps away from one another. Eg. a “C” to “G” step-wise movement is as follows:

C (1 step), D (2 steps), E (3 steps), F (4 steps), and G (five steps). This equals five steps or scale degrees. So if you travel clockwise from “C – G – D – A – E – B – F sharp – C-sharp,” you will notice that there are seven keys. Each of these keys is five steps (or five perfect fifth intervals) away from one another. C has no sharps or flats. G has one sharp, D has two sharps, A has three sharps, E has four sharps, B has five sharps, F-sharp has six sharps, and C-sharp has seven sharps.

If you move counterclockwise (or anti-clockwise as the British say), then you move from C (no sharps or flats) to F (one flat), B-flat (two flats), E-flat (three flats), A-flat (four flats), D-flat (five flats) G-flat (six flats) and C-flat (seven flats). Some of the keys near 5, 6, and 7 o’clock are more or less academic. They are rarely used, except perhaps in advanced repertoire.

Some of these keys are enharmonic too. That means that there are two names for each key. There is a sharp name and a flat name. There are three enharmonic keys. They are:

1.) B (C-flat)

2.) G-flat (F-sharp)

3.) D-flat (C-sharp)

All of the keys moving clockwise or counterclockwise (as described above) are major keys. For every major key there is a relative minor key too. The minor keys are inset, and appear smaller in the diagram. To find the relative minor key, chose a letter (or key) and move six steps up (a major sixth) or three steps down (a minor third). For example, C to A is:

C (1 step), D (2 steps), E (3 steps), F (4 steps), G (five steps), A (six steps). Again, this is ascending. Conversely, you can move down from C as such: C (1 step), B (2 steps), A (3 steps). Notice how we always count the starting point as the first step. In this example, it is the note “C.”

But what does the circle of fifths ultimately tell us?

The circle of fifths ultimately helps us to understand the relationships between keys by proximity. C and G, for example, are quite close. They are right next to one another. Their major scales share the exact same set of notes, except one pitch. C major uses “F,” and G major uses “F-sharp.” Because these keys are so close, they also share many of the same chords and musical cadences. A cadence is a harmonic configuration that creates a resolution or finality to the “tension” of the moving chords. Cadences bring the music “back home,” as it were, to its tonal center. The circle of fifths also shows us the relationship between relative keys (see above).

For example, C major and A minor share the exact same note set. A minor key may contain some variations called harmonic minor and melodic minor. However, A natural minor contains the same set of seven notes as its parent key: C major.

Let’s look at this:

“C, D, E, F, G, A, B” are the seven notes that make up the C major scale. “A, B, C, D, E, F, G” are the seven notes that comprise the A natural minor scale. The order of the notes is different, but the pitch set is identical. In this case, these are all the white keys on the piano.

Musical keys located far away from one another on the diagram are called “remote.” These keys have very different sets of notes and they don’t interact as well. This is another critical feature of the circle of fifths. By understanding the proximity of the keys, a composer can see which keys best interact or fit together. C and G or C and D, for example, interact well. C and F-sharp or C and D-flat do not interact well.

A lot of music uses modulations or key changes, too. A composer can move much more smoothly to a key that’s closer on the circle. In this sense, the circle of fifths helps composers understand how to make more meaningful and cohesive key changes.

Refer to the circle of fifths anytime you want to understand the relationship between keys, scales, and chords. It’s the best tool you can use to write or analyze music.

Eric Starr